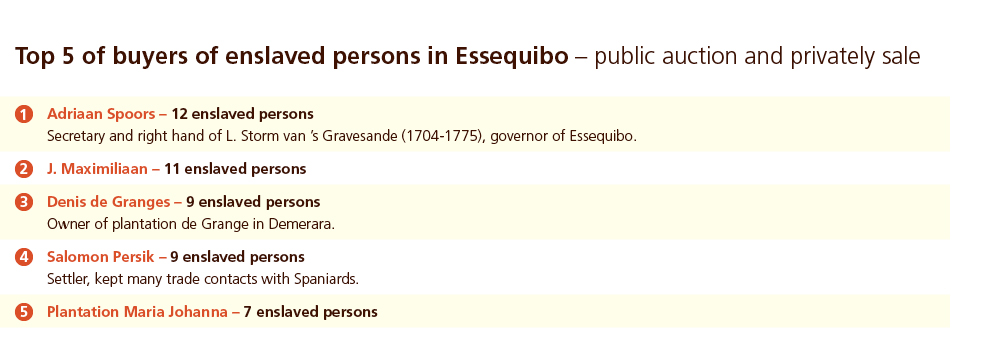

When The Unity had only just arrived in the Berbice Colony, captain Menkenveld had already written his contact in Essequibo. In the letter he inquired after the prices of the enslaved people in Essequibo. His contact’s name was Adriaan Spoors, a secretary in the service of the West Indian Company (WIC).

Pregnant

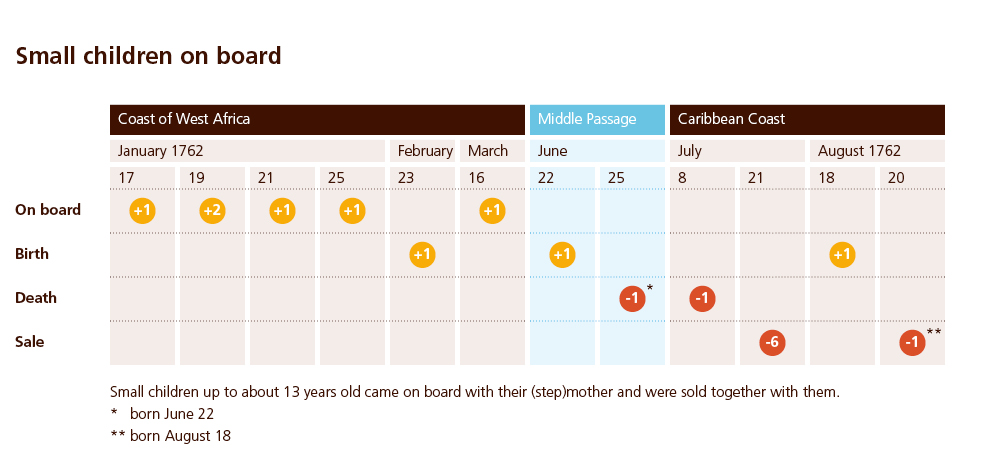

On August 18, one day before the auctions, one of the African women gave birth. She was allowed a day of rest, after which she was sold privately on the 20th of August. As per usual, the child was auctioned together with the mother. The two were the last enslaved persons to be sold.

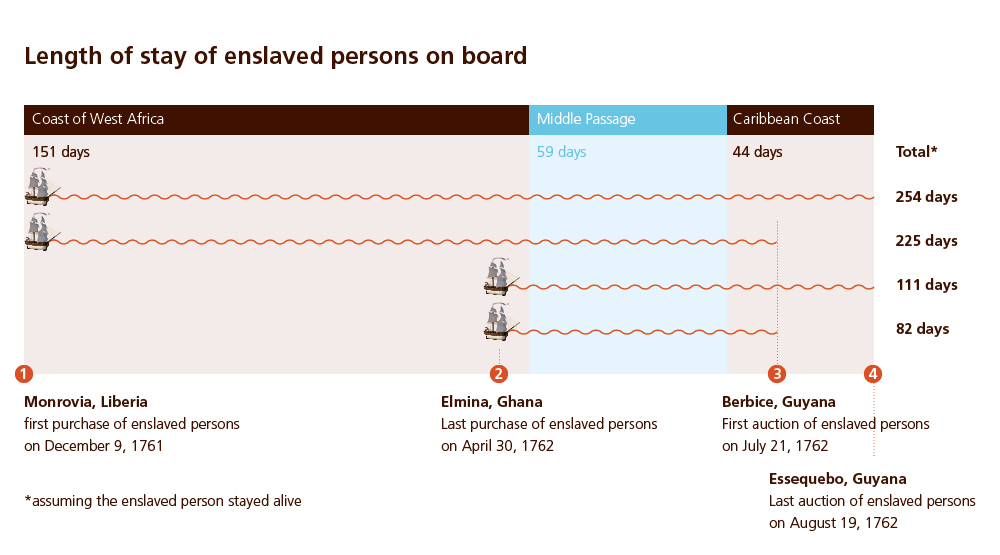

In total, 47 men, 58 women, 15 boys and 1 girl were sold at the two auctions. Privately, 6 men, 10 women, 3 boys and 3 girls (a total of 12 Africans) were sold.

Enslaved People for Sale

On August 19, 1762 two auctions were held. During the first public sale 80 enslaved persons were sold, and during the second one 40. On the same day 21 enslaved persons were sold privately as well.

In total, 47 men, 58 women, 15 boys and 1 girl were sold at the auctions. In addition, 6 men, 10 women, 3 boys and 3 girls were sold out of hand.

Sugar and Bills of Exchange

In the further particular instructions the MCC outlined its preferred method of payment for the bought Africans:

“on condition of payment in sugar which will will be loaded on Your Honour’s ship as soon as possible. Otherwise, you can pay in bills of exchange”

The MCC made the buyers of enslaved people in Essequibo partially pay in Sugar. The payments needed to be satisfied in three installments. The first installment had to paid three months after the purchase. The MCC determined that this payment had to be made in sugar: at least two hogsheads of sugar per enslaved person.

The company reckoned a set price of 75 guilders per hogshead of sugar. If the sale of sugar fetched more money, the difference was paid to the buyer of the enslaved African. If the hogshead fetched less at the Middelburg auction, the buyer had to compensate for the difference. Buyers were also allowed to pay in coffee beans or other plantation products. Moreover, the cargo had to be brought to the ship, and the transportation and insurance costs were also charged to the buyer’s bill.

The second and third installments could be paid in cash or bills of exchange, unless the MCC decided to send a return ship for the third installment. In that case it had to be paid in sugar as well. The last two installments were four months each, so that the entire debt had to be paid within eleven months after purchase.

A total of 121 enslaved Africans were sold in Essequibo, so in theory The Unity should receive 242 hogsheads of sugar or other goods of the same value on board. In the end she actually received 176 whole and 17 half hogsheads of sugar, 84 bales and 5 barrels of coffee beans and 156 rolls of tobacco.

Departure from Essequibo

In his letter to the MCC directors, captain Menkenveld wrote that he was doing his uttermost best to sail the loaded vessel to the fatherland as quickly as possible: “I will do my utmost best to load the ship as quickly as possible in order to be ready to sail from here.” Yet he was not willing to pay any price for his cargo: “I would be able to take in my entire cargo, but the exorbitant costs do not allow for this”.

In the most favorable circumstances, The Unity would have been able to depart after the first installments had been paid: November 20, 1762, three months after the last enslaved persons had been sold. Departure was delayed for another month however. Only on December 17 did the captain receive the last hogsheads of sugar and bales of coffee beans. The next day the pilot came on board to sail the ship upstream. Pilot Jan Willemszoon brought The Unity to the mouth of the Demerara river in Guyana. The boat and rowboat were taken in, after which the voyage home could begin.

Plantation in the Caribbean

Fragment of a large map of a Caribbean plantation, including a statement of letters, a survey drawing, an alliance insignia and ornamental details. Drawing on parchment by N. Keiberg, 1700-1800, 28.6×67.2cm. Rijksmuseum RP-T-1969-6.

Plantation in the Caribbean

Detail of a fragment of a large map of a Caribbean plantation. Drawing on parchment by N. Keiberg, 1700-1800, 28.6×67.2cm. Rijksmuseum RP-T-1969-6.

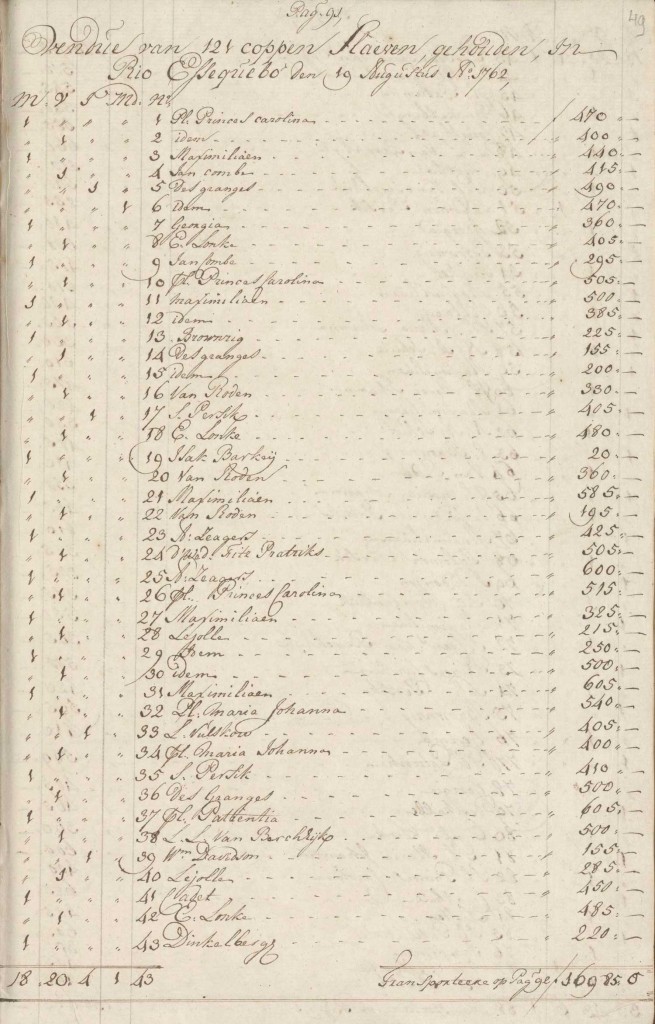

Auction report in Essequibo

First page of the report of the auction of enslaved Africans from the ship The Unity. Zeeland Archives, Archives of the MCC, inv.nr 384.