By the the time The Unity departed from Africa, most of the enslaved Africans had already been held captive on board for several months.

Locked up for months

The last enslaved person had come on board a week before departure from Africa, whereas the first, an African man, had already been bought on December 9, 1761. He had been locked up for 150 days before the Unity set sail – if he had stayed alive all that time. It can not be determined whether this was the case: the captured Africans were not noted down with a name or unique number in the administration of the Unity.

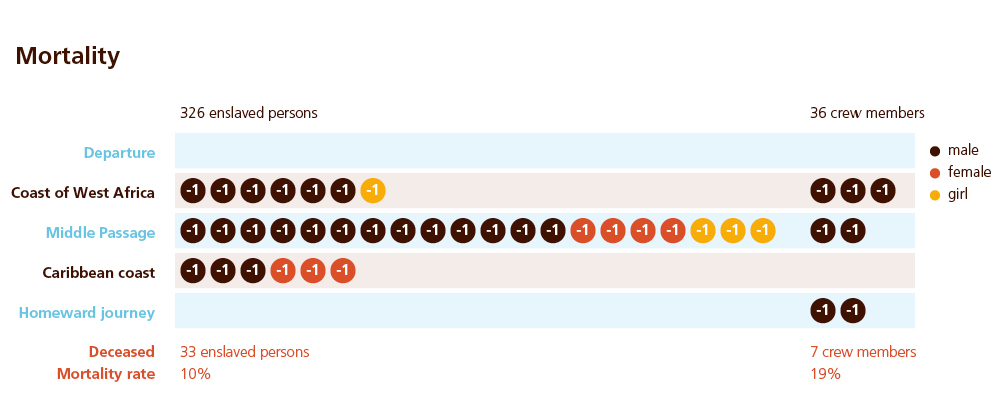

Seven Africans died during the ship’s stay at the coast of Africa: six men and a girl. The remaining 319 men, women, boys, girls and small children had their last view of the African coast on May 8, 1762. (Males were deemed men from the age of 18 onwards; women from the age of 13 onwards.)

Men separated from women

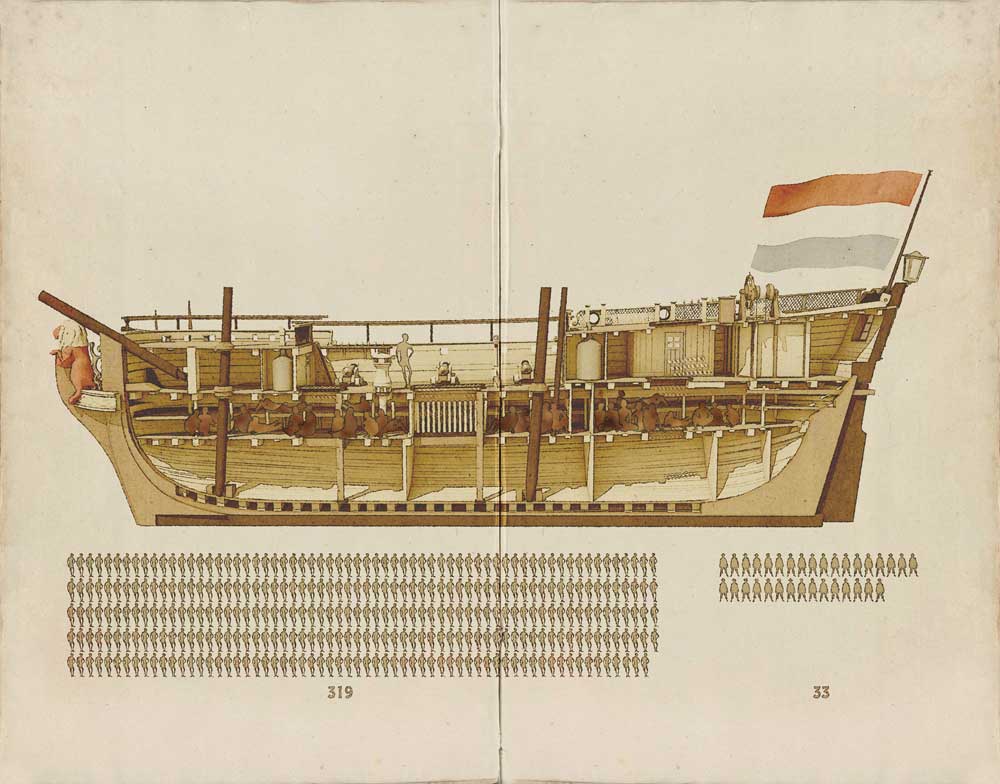

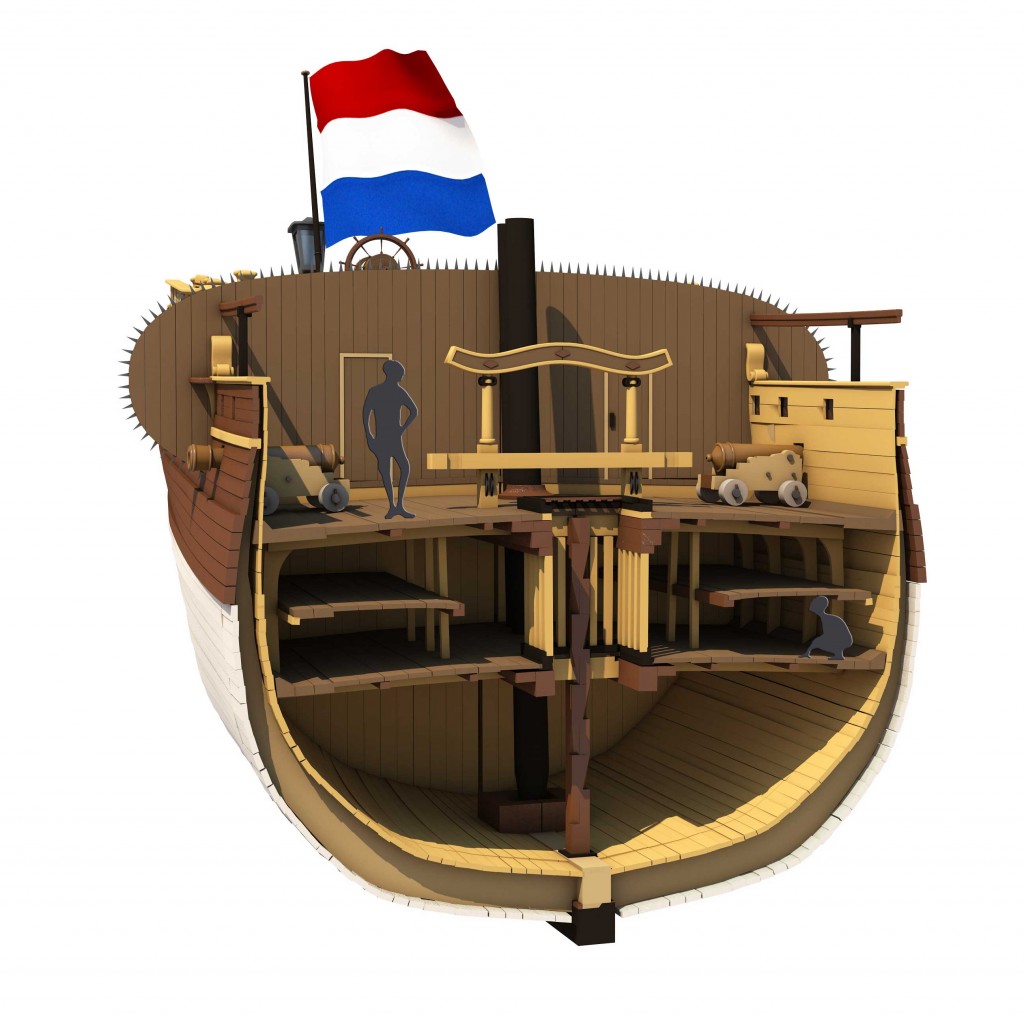

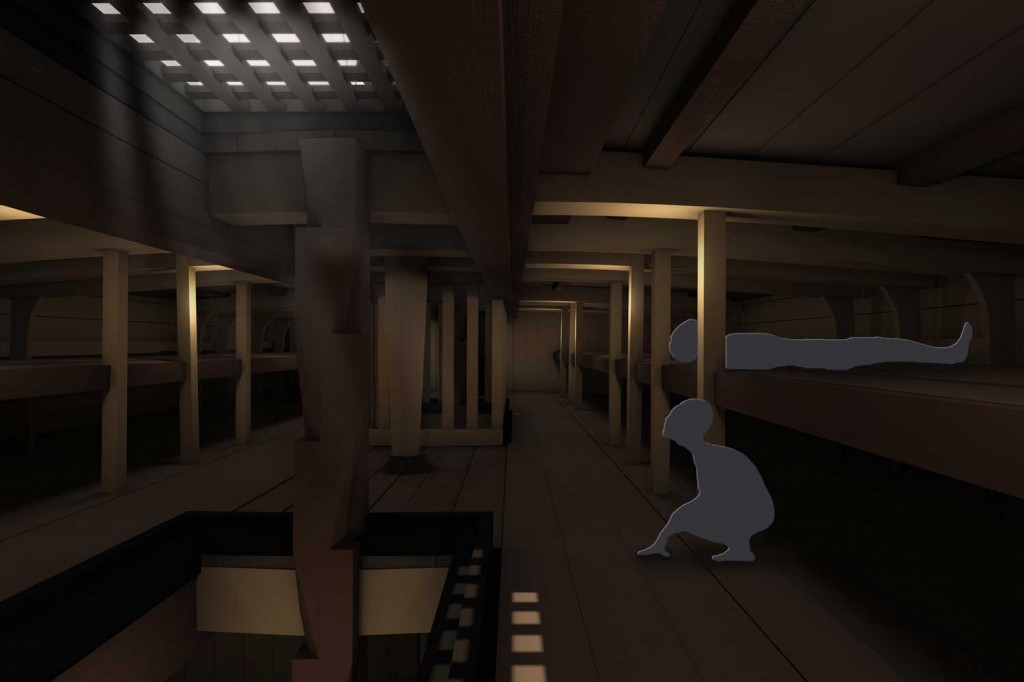

The men and the boys were held separately from the women and girls. The former were locked up on the ‘tween deck in the fore body. During the day – if the weather permitted it – they were allowed outside on the waist deck.

During the evening and the night the women and girls were locked up on the ‘tween deck in the stern. During the day they were allowed to go to the ‘tent’, a wooden hut made by the carpenters during the voyage, which was put on the aft deck.

Guarded

A wooden partition was placed behind the main mast between the fore body and the stern. This was to prevent the African men from entering the stern with the African women and the living quarters of the officers. A door had been placed in the partition which was guarded by a sailor with a cutlass, a short flat sword.

Shackles

It is not known if the captured Africans were shackled the entire time they were on board. The ship’s inventory notes one ‘slave chain’, 110 leg cuffs and 30 handcuffs.

According to the 18th century ship’s doctor Gallandat the men were shackled together. The ship’s surgeon was to ensure that they were released from their shackles at the first signs of any illness.

Modern literature on the trans-Atlantic slave trade holds that women were not chained down, and the men only when the ship neared land, or in case of impending revolts. This view is confirmed by the surgeon of the Unity. In his journal Petrus Couperus wrote that an African man ‘was put in shackles’ because a rumor went round that he wanted to jump overboard.

Nourishment

Gallandat attributed an important role to the surgeon on board, also with regard to nourishment. “They [the surgeons] have to put their minds on everything that can lead to their [the enslaved Africans] preservation in any way and to do everything in their power to alleviate their sad fate: to that end the commanding officers have to buy fresh products which the surgeon deems necessary for the slaves and to ensure that they do not lack water.”

At 11 o’clock in the morning the prisoners on board of the Unity received their main meal, which usually consisted of barley, horse beans and water. The food and drinks were handled with care. The water for cooking the barley, for example, was diluted with a quarter part of salt water.

According to the 18th century Zeeland ship’s doctor Gallandat the enslaved Africans were supposed to eat twice a day: ‘in the forenoon with barley, and in the afternoon with horse beans, or one day with horse beans and the other day with barley’. With the exception of a little bit of lime juice or wine as medication, water was the only thing they were given to drink.

Hygiene

The captives could barely stand or lie down in the cramped space between decks. Hygiene on board will therefore have been abysmal, despite the regular cleaning. During the Middle Passage the slave quarters between decks were cleaned weekly and smoked with juniper berries and incense against the stench. On the other days, the quarters were sprinkled with lime juice.

Sick

According to the 18th century ship’s doctor Gallandat the surgeon was supposed to visit the slaves a strictly daily basis, “and to maintain a special care and attention concerning the sick:

in some ways they have to be like fathers to them; they have to provide as much convenience as possible; they have to take care that they are released from their shackles, not only when they are sick, but also when they have any disposition to be sick or get scurvy, and when they are sad, which usually predicts an oncoming disease.”

The surgeon on board the Unity, Petrus Couperus, seemed to follow Gallandat in this. At the very least he tried to establish the cause of death of all deceased Africans, although he hardly succeeded in doing so. In his journal Couperus described the diseases as well as possible. His descriptions provide some more insight into his personality and into the general situation on board. For example:

“A male slave, who had refused to eat since had been bought, passed away. Since he was losing his strength I constantly tried to bring him to eat” – May 18, 1762

“A female slave from the Windward Coast died […] always appeared to be mourning: she sat very still and talked little. She did Always eat and drink Always […] I believe that her melancholy started because she has had a child, and the negroes had kept it on the coast” – May 30, 1762

Sometimes Petrus Couperus took a step further in determining the cause of death:

“A female slave died. She had been beaten about four weeks before she passed away, and blood had been running from her ear […] I asked the captain if I could perform an autopsy on her to discover the cause of her quick death, and he gave me permission. Assisted by my mate I made a large incision to the ossa tempora” – June 13, 1762

This was followed by a detailed description of the situation underneath the skull. Moreover, we can infer from his description of this patient that there was a water barrel in the quarters for the women and girls:

“After that she tried to go to the water barrel to drink, but she could not get up without throwing up. She went back upstairs after this” – June 13, 1762

Life and death

The loss of lives during the Middle Passage of the Unity was not particularly large for those times: twenty enslaved Africans and two crew members passed away.

The bodies of the deceased Africans were probably put overboard without any kind of ceremony. 13 men, 4 women and 3 girls died during the Middle Passage. One of the women had just given birth to a baby.

The surgeon and the first mate did not always record the same date of death. Sometimes the date is one day off. The journal of the first mate is followed for the blog.

- On May 18 a man who refused to eat passed away

- On May 19 an emaciated man got a seizure before dinner and fell down dead

- On May 30 a woman of the Windward Coast died of ‘melancholy’

- On June 7 a man was found dead between decks

- On June 9 an emaciated man from Butre died

- On June 11 a woman with many complaints of headaches suddenly passed away

- On June 13 a woman who had been beaten aboard died after she had to vomit during eating

- On June 13 a man with fever died on the lavatory

- On June 16 an old man from the Windward Coast died of dysentery

- On June 20 an emaciated girl who never complained got diarrhea and passed away

- On June 22 a man who wanted to go to the lavatory got a seizure and fell down dead

- On June 23 a coughing man with complaints of chest pains and tightness died

- On June 23 an emaciated girl got diarrhea died

- On June 25 a newly born baby, a girl, passed away

- On June 26 the mother of the deceased baby of June 25 died

- On June 26 a man who had had diarrhea for over two months passed away

- On June 28 an old man who complained of tightness and coughing died

- On June 30 a man who complained of chest pains and tightness died

- On July 1, a girl who had suffered from sleeping sickness for five weeks passed away

- On July 2 a man who complained of chest pains and who refused to eat passed away

- On July 3 a man who had suffered from congestion for two months died

Watch the video on the introduction page.

Cross-section of the Unity with view of the bunks for the slaves on the ‘tween deck. The partition can be seen above the ‘tween deck behind the main mast.

‘Tween deck with bunks

Reconstruction of the ‘tween deck underneath the waist deck in which bunks were made.