On departure the crew of the third voyage of The Unity numbered 36, the exact average of an MCC triangular voyage. There were usually more crew members than for a return voyage to West Africa or to West-India. A voyage with enslaved persons from Africa to the Caribbean was more dangerous and took longer.

Crew of The Unity

Ten of the men on board had known each other for years, among them the officers. They had gone on several voyages with each other and had risen in the ranks together. The current first mate Daniël Pruijmelaar, for example, had started out as sailor on a ship where The Unity’s captain Menkenveld was a first mate.

At the muster on 7 September 1761 the crew of The Unity existed of 37 heads. Behind every name the monthly wage in guilders and the place of origin, with a note stating that the person could have been living in Zeeland for years, was given. The men whose names are given in bold, have sailed together before under captain Menkenveld.

- Captain Jan Menkenveld, from Hamburg, f 60

- First mate Daniël Pruijmelaar, from Middelburg, f 36

- Second mate Johannes Franciscus Schutz, from Doornik (Flanders), f 30

- Third mate Adriaan de Puijt, from Goes, f 24

- Surgeon Petrus Henricus Couperus, from Nieuwland (Walcheren),f 36

- Surgeon’s mate Louis Bernard, from La Rochelle, f 18

- Master carpenter Paulus Christiaan Kemp, from Hamburg, f 38

- Carpenter’s mate Pieter de Gerol, from Middelburg, f 20

- Boatswain Pieter Pieters, from Groningen, f 24

- Boatswain’s mate en zeilmaker Hans Kramer, from Copenhagen, f 20

- Head cooper Adriaan Hillebrand, from Veere, f 24

- Cooper’s mate Isaac de Vos, from Middelburg, f 18

- Cook Thomas Ditmars, from Hamburg, f 23

- Corporal (smith) Coenraed Meijer, from Amsterdam, f 22

- Sailor Jacobus Rankin, from Veere, f 17

- Sailor Jacobus Duijnkerke, from Aardenburg, f 16

- Sailor Pieter de Graaff, from Middelburg, f 15

- Sailor Roelof Siebers, from Breidvik, Norway, f 17

- Sailor Maarten Capper, from Flushing, f 17

- Sailor Cornelis de Hond, from Willemstad, f 17

- Sailor Arnoldus Machielsen, from Veere, f 17

- Sailor Alonso Madroes, from Cadiz, f 16

- Sailor Carel Hutte, from Nijmegen, f 17

- Sailor Anthonie Colombo, f 17

- Sailor Jan Ewaard, from Veere, f 16

- Sailor Abraham Campus, from Goes, f 14

- Sailor Philippus de Voogt, from Blankenberg, f 15

- Sailor Abraham Vermeulen, from Schoondijke, f 15

- Sailor Anthonie Battram, from Heine near Hannover, f 17

- Sailor Otto Westman, from Stockholm, f 17

- Sailor Johannis Coijwijk, from Middelburg, f 16

- Sailor’s mate Herman Laars, from Flushing, f 10

- Sailor’s mate Adriaan de Visser, from Nieuwland (Walcheren), f 11

- Ship’s boy Albert Vermeulen, from Flushing, f 7

- Ship’s boy Gilles Lint, from Flushing, f 5

- Ship’s boy Lieven Lambregts, from Flushing, f 8

- Ship’s boy Philippus de Bock, from Brussels, f 7

Muster of crew

The officers were contracted by the directors before hand. Captain Menkenveld was given the position of captain on the next voyage a week after returning from his previous voyage on 14 July. On Tuesday 21 July he was hired for the third voyage of The Unity along with first mate Daniël Pruijmelaar, surgeon Petrus Couperus and second mate Willem de Molder.

The second mate was given a discharge on 11 August. He was offered a financially more attractive position as first mate on the ship Zeeburg from bookkeeper François Gaaswijk. Gaaswijk was also an important supplier of trade good for MCC ships. The directors were annoyed and made clear that he would never be given a position on one of their ships again. (This was not true: Two years later Willem de Molder became captain at the MCC.)

After the discharge of De Molder the third mate and the master carpenter’s mate moved one position up. Johannes Schutz, who had already applied on 20 July, promoted to the position of second mate and Adriaan de Puijt became third mate.

The French Louis Bernard from La Rochelle applied during the following meeting, on 18 August, for the position of surgeon’s mate and was hired immediately.

For the muster of the entire crew, on Monday 7 September, drums were played in Middelburg and Flushing. The muster included the reading aloud of the contract and the signing of this contract by the crew.

Contract

The contract contained regulations and rules (of behavior) and fines in case of offence. It also included the arrangement concerning the ‘slave money’: for every enslaved person who was sold in the Caribbean the MCC paid a bonus.

The reading of the contract was done by waiter bailiff Lodewijk Koorn. “Articles and orders according to which we, officers and sailors were hired on the ship named The Unity, captained by Jan Menkenveld”. This was the very first sentence. The destination followed – “the coasts of Africa and America” – and then the rules which all the people on board have to follow.

The contract was partly printed. Information for every specific voyage was filled in by hand in the parts that had been left open and at the bottom of the contract. Underneath you can find the contract point by point. The rules that were specific for the third voyage of The Unity are given in italics:

- At the time of departure, we will voluntarily bring the ship to the Vlacke and at the time of arrival, we will unload as much as is needed for the ship to be brought into port.

- The officers and sailors are allowed to bring cargo along as specified below, provided that this cargo does not consist of alcohol, gunpowder, guns, or contraband.

- In order to keep the order and discipline on the ship, we promise to follow all orders and commands to the service of the ship in all obedience and without protests given by the captain or whoever is commissioned in his place to represent his person, as well as his officers, each in their qualities and services. We promise to behave ourselves both on the sea and on the land as honest officers and sailors throughout the journey.

- We will help load, unload, propel, with the ballast.

- Keel the ship and clean her, scrape her outside and inside.

- We will transport goods with barques, the boat and other vessels from and to land or other ships.

- One chest will be used per two sailors.

The fine for refusing to work was 6 guilders, which was for the benefit of the ‘sailing poor.

- We have been paid two months in advance.

- Our monthly wages will commence as soon as the ship has reached the sea beyond the last buoy, and end when the ship will have arrived safely and will have been moored at the Vlacke; no sooner than that may we request our salary.

- It is also emphatically stipulated that should the ship sink or be taken by the enemy during the journey, we are not entitled to our monthly wages, but be satisfied with the advance we received.

- The captain is free to distribute the wages partly according to his own insight.

- Should it happen that enemies attempt to damage or take over our ship during the journey, we promise to defend the ship and our captain at risk of our lives.

- The coward deserter who will lose his wages as well as his personal belongings.

- The captain promises that he who becomes lame or wounded as a consequence of defending the ship will receive treatment paid by the revenues of the journey and according to the laws of the sea. If treatment appears ineffective, a compensation, can be provided

- Everyone should be contented with the ration of food and drinks that the captain and the officers will allow. Protesting against this will result in a fine of one month’s wage.

- Everyone should be present at the daily prayers with proper reverence, on forfeit of 6 shillings given to the sea crew’s poor. No one is allowed to leave the ship and spend the night elsewhere without the permission of the captain or his substitute, on forfeit of 6 guilders for the sea crew’s poor.

- Becoming drunk, fighting, or any other form of profligate behavior both on the ship and on the land is forbidden on forfeit of 6 guilders give to the sea crew’s poor. The captain is free to remove anyone from the ship without paying him a penny of his earned wages

- He who will desert during the journey before having reached this city or the final port, will forfeit all of his monthly wages.

- Next to what has been mentioned in this document, we will adhere to the customs and sea laws usual of this city, including its fines and punishments as related to persons and goods.

- No one, be they captain, officers, sailors, or ship’s boys, is permitted to trade ivory, wax, pepper, enslaved persons, or any other goods bought on the coasts, on forfeit of all their monthly wages.

- Neither the captain nor his mates, nor the chief surgeon are permitted to take bring along cargo for their private account, nor are they permitted to trade or sell enslaved persons, on forfeit of 1000 guilders for every traded or sold enslaved person. In addition, all their monthly wages and premiums will be confiscated.

- On the other hand, for every enslaved person that will be sold in the colony, the captain, the mates and the surgeon will receive the following amounts after they have returned: the captain 80 shillings per enslaved person, the first mate 24 shillings, the second mate 10 shillings, the third mate 6 shillings and the chief surgeon 24 shillings.

- Only goods are allowed to be taken home, gold and silver are prohibited.

- At the time of return, everyone will have to pledge that he does not own prohibited goods. If this is the case, all the shipped cargo, the monthly wages, and premiums will be forfeited

- The other members of the crew are allowed to bring cargo with them. The ship’s carpenter and the boatswain: per person goods worth f 400, containing no more than 3 kelders or 6 half anchors of liquor, including the alcohol for own consumption. The cook, the boatswain’s mate, the surgeon’s mate, the corporal and the cooper: good worth f 200, Containing no more than 2 kelders or 4 half anchors of liquor, including the alcohol for own consumption. The sailors and ship’s boys: good worth f 75, Containing not more than 1 kelder or 2 half anchors, including the alcohol for own consumption.

After the contract had been read out loud, the crew signed the document, usually with their name or, if they could not write, with a cross. Seven members of the crew of The Unity could not write: the cook, 3 sailors and 3 ship’s boys. First the higher officers signed, follower by the lower officers, with exception of the head carpenter’s mate. He signed as one of the last people surrounded by the crew.

Wages and bonuses

All members of the crew received a salary. As can be read in the contract, the higher officers could claim a percentage of the sale of every enslaved person sold (‘slave money’). In case the voyage made a lot of profit, they could also claim a percentage of that profit (recognition). The captain received the highest wage and also the highest percentages of ‘slave money’ and recognition.

However, the higher officers were not allowed to take any cargo with them. The other members of crew were allowed to do so, up to certain amounts, as can be seen in the contract. They were, however, not allowed to trade these good in West-Africa. Apparently the trading of these goods in the Caribbean, for example for products from the plantations, was allowed. The space for personal possessions or cargo on board of the ship was not unlimited. The officers were allowed to bring a ship’s chest per person. The sailors had to share such a chest per two persons.

The dangers on board of a ship were taken into account in the caculations of the wages and the bonuses. Work on a ship was heavy and with this many captives on board created a greater risk of disturbances. Captain Menkenveld had experienced three uprisings by enslaved Africans.

Personal matters

In the weeks previous to the voyage the members of the crew said their goodbyes to family and friends and made arrangements for the time that they would be away from home or in case they would not return. The dangers at sea were grave. Copies of notarial pieces and of last wills of some members of the crew have been preserved. In these documents they authorize their wives to act in their place and they named their heirs.

Life on board and on land

From a few members of the crew we know more about their work and life. This information, as far as is known, is given below in order or rank:

Captain Jan Menkenveld was an emigrant from Hamburg, Germany. When he mustered with the MCC he was approximately 30 years old and had already made a career. When he started his career with the MCC he started immediately as first mate. He remained in this function for the first two voyages, after which he became captain in 1752. He established himself in Middelburg for good and became a member of the Lutheran church. According to his life certificate, which has been preserved, he came from Gluckstadt, a city not far from Hamburg on the Elbe river. Menkenveld was married to Cornelia de Molder.

The captain was in command of the ship, or as Menkenveld put it himself: “I am sovereign, lord and master on my ship. No one, not even the governor, has anything to say about me”. He left no doubt about who was in charge.

The third voyage of The Unity was the fifth voyage of Menkenveld as captain. The next journey would be his last: he was fired for fraud and misdemeanor.

First mate Daniël Pruijmelaar was from Middelburg. He started his career at the MCC as a sailor and in 11 years he climbed up to the function of first mate. He was married to Cornelia Flinck and lived in Middelburg. The third voyage of The Unity was Pruijmelaar’s third voyage as a first mate. The next voyage he would undertake would be as captain on The Unity.

Surgeon Petrus Henricus Couperus was originally from Heeg, Friesland, the Netherlands. His father was a preacher in the community Wymbritseradeel, Friesland. Couperus started his career at “‘s lands hospitalen te velde”, which probably was a hospital of the VOC (the Dutch East India Company). Afterwards he became a surgeon on the VOC ship The Saamslag. He moved to Veere, Zeeland, the Netherlands, and married Margarita Anderson. He then worked some years on land on Walcheren; in Nieuwland and Grijpskerke, villages in Zeeland. He tried to establish himself as the second surgeon of the village Arnemuiden in Zeeland, but he was rejected.

In 1758 he started his service as surgeon with the MCC. In 1760 the couple moved to Middelburg. Couperus went on two voyages in service of the MCC before he went on the third voyage of The Unity. One week after departure he turned 37 years old, a respectable age for a member of the crew. The surgeon’s journal that has been preserved has been written by him.

Sailor Anthonie Battram was from Heine near Hanover, Germany. He mustered and signed the contract, but at departure he failed to appear. Under his name in the ship’s wage book the word ‘ran away’ was noted down. In a copy of the muster roll the word ‘absent’ was written and Battram’s wage was taken back. In another copy the reason as to why Battram had stayed away becomes clear: ‘did not come on board due to illness’.

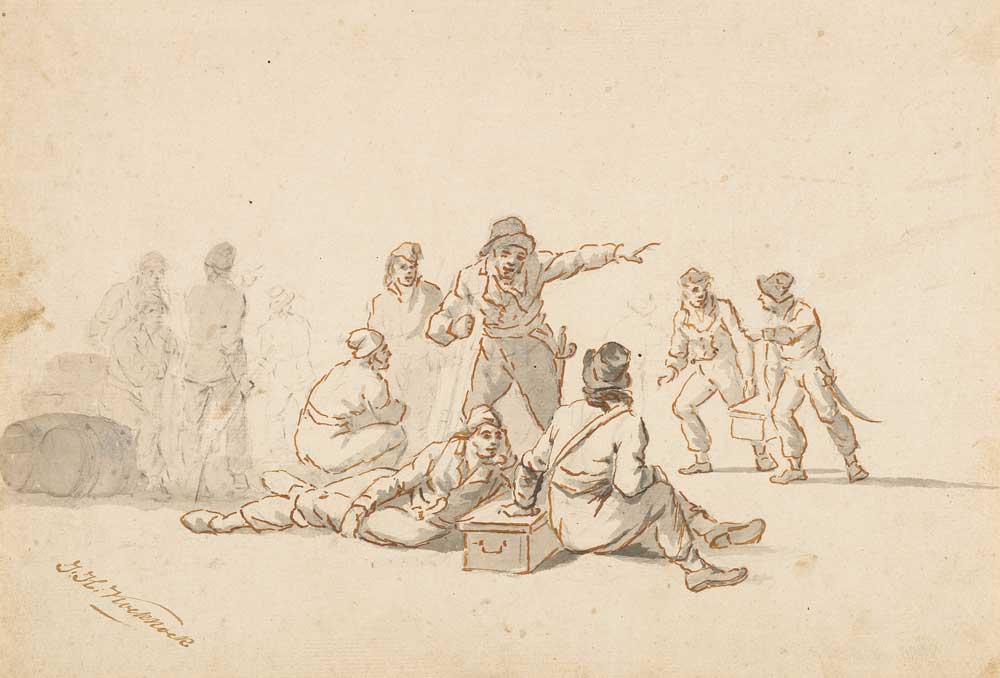

Mustering of crew

J.H. Koekkoek (1778-1851), drawing, potlood, pencil in brown, washed gray, 23.5 x 34.5 cm. Zeeland Archives, Zelandia Illustrata III, inv.nr 1010.

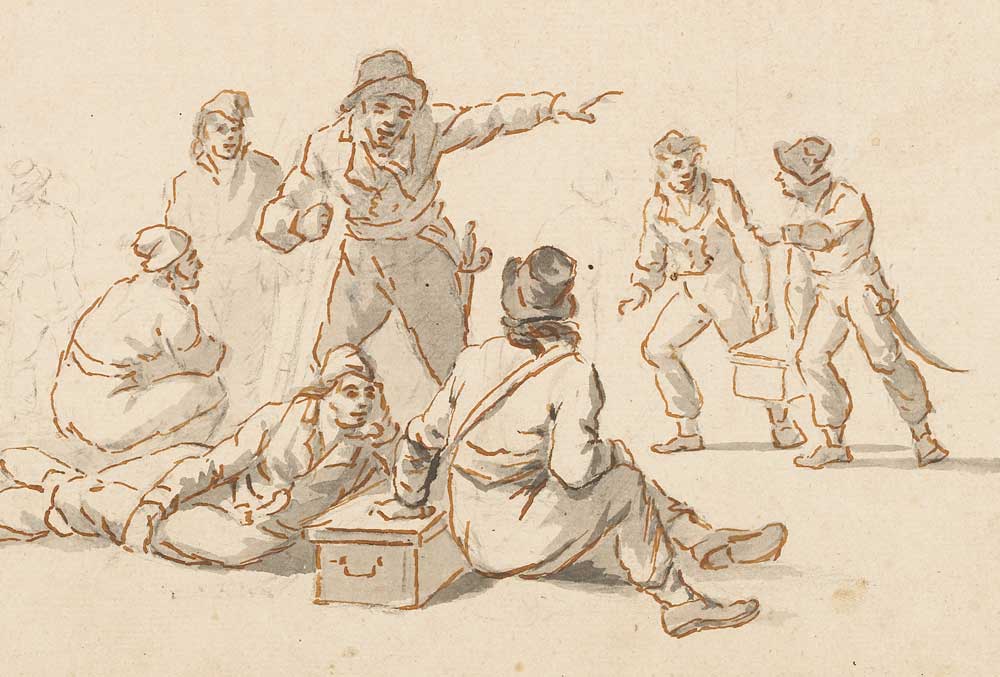

Seamen with chests

Detail from the drawing above by J.H. Koekkoek (1778-1851). Zeeland Archives, Zelandia Illustrata III, inv.nr 1010.

Sailor

Stippelets and aquatint by M. Sallieth after a drawing by J. Perkois (1756-1804) and J.H. Prins (1757-1806), 21.2×16 cm. From 1818 onwards the engraving also appeared as part of a series of 33 engravings by Mathias de Sallieth, bound in: Perkois, Jacobus, Prins, Johannes Huibert, Collection of variously clothes male and female figures, for the practice of young painters and enthusiasts (Rotterdam: Johannes Immerzeel, 1818). Rijksmuseum RP-P-OB 60.400

Seal captain Jan Menkenveld

The seal in wax of captain Jan Menkenveld. Zeeland Archives, Archives of the MCC, inv.nr 376.