On December 26th, 1762, The Unity passed the island of Barbados, the eastern-most island in the Caribbean. After Barbados, the wind picked up forcefully, and remained that way for the following months. Towards the end of January the ship wound up in a heavy storm. It began in the early morning of January when the wind picked up to a storm. On board the shutters were fastened securely. Of the sails, only the main staysail could be put out.

Heavy Weather

The waves rose higher rand higher rand hit the decks with a crushing force. A heavy canon (which used three-pound canon balls) was smashed out of its supporting gun carriage, and disappeared in the waves. The water was beginning to penetrate cracks in the ship, and the water level in the holds was rising to alarmingly high levels. That evening and night the crew pumped out water continuously, with both pumps. Attempts at turning the ship before the wind failed, at which point the main staysail was also put up – the ship was now sailing with completely furled sails. “Will sail the ship with furled sails and wait out the NNW to NW storm, trusting to God’s grace”, as captain Menkenveld puts it. The next day the force of the wind was reduced, but the weather remained bad, with occasional “heavy squalls of rain, wind, hail, snow and strong lightning.”

Forced Stay

The Unity finally reached The Channel on February 13th, 1763 – though the problems did not end yet. Due to the wind and storm the ship threatened to hit the lee shore. At daybreak, The Unity found itself between the port of Plymouth and the lighthouse Edystone. Menkenveld consulted with his highest officers, and together they decided to enter the English harbor: “resolved […] to enter the first possible harbor to save the ship, even while the storm could be detected in the sky.”

The captain fired four canon shots for a pilot, who brought the ship safely into the ‘Oostcoffer’ harbor of Plymouth. Seven English ships entered the harbor together with The Unity. In the Oostcoffer the captain also met fellow Dutchmen, such as captain J.J. Jonker, of the frigate The Spy, who had come from Sint Eustatius and hailed from Rotterdam. Another fellow countryman, captain Coenraad de Wolff, of the Middelburg snow ship the Petronella Cecilia, had fallen ill, as well as the rest of his crew. They had had a long return voyage, and were trying to recuperate in the harbor.

The captain went ashore on February 16th, 1762, while The Unity received local ‘guards’ on board. Undoubtedly these ‘customs officials’ were there to check that cargo goods were not traded off board – since that was forbidden by law. In the meantime, the bad weather continued to lead many other ships into the harbor, such as a Dutch barquentine which had lost its main mast, and a Middelburg snow ship which had lost both of its masts.

Coldest Month of the Century

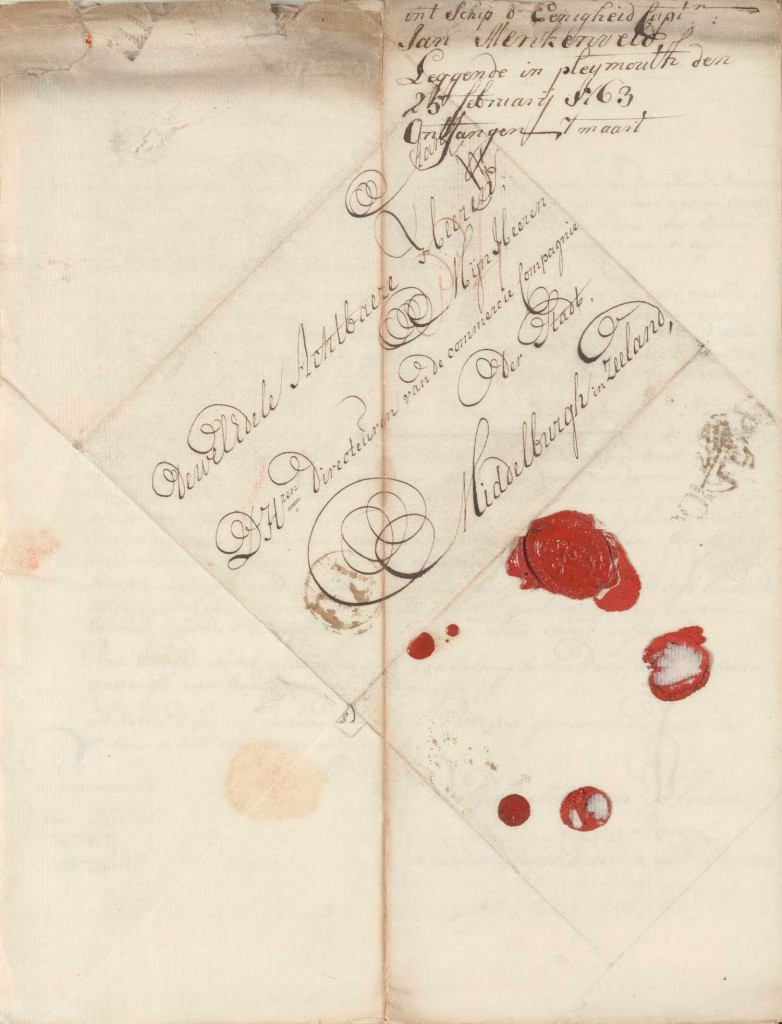

In his letter of February 18th, 1762, Menkenveld spoke of his hope to be in Middelburg in little more than a week: “Hope that, with the Almighty’s blessing, I can resume the voyage in 8 to 1- days, in order to return with the full moon”. That wish would remain unfulfilled: until March 20th the weather would remain invariably bad.

The winter of 1762-1763 would enter the books as a very severe winter, and the month of January as the coldest of the century. Throughout Western Europe rivers and inland bodies of water had frozen shut, including the Thames in England and the Sont between Sweden and Denmark. The Rhine river in Germany was crossed on foot at Cologne, and in Hamburg horse-pulled wagons could even cross the river. In the Republic it was possible to travel between Friesland and Holland by sled. The temperature remained below zero continuously for most of that winter, usually between -5 and -12 °C, only occasionally interrupted by a few days of thaw.

Source: Buisman, J., ‘Bar en boos: Zeven eeuwen winterweer in de Lage Landen’ (Baarn 1984)

Clothes for the Crew

The crew of The Unity was exhausted. The harsh voyage from the Caribbean, together with the bad weather, had required the utmost. The captain went out for provisions, buying both food and clothes for the crew. The week’s rest in the harbor of Plymouth did the crew good, and they quickly recuperated.

In his next letter to the directors, on February 25th, 1763, captain Menkenveld spoke again of being able to return home quickly. The fault would not lie with his crew: “since my crew is now more refreshed than at my arrival here. Although they were never sick, they had been wearied out by the cold and lack of rest, and too little clothing, with which I now provided them. Now they could face a small crusade.” The crew was expanded by one crew member, another sailor, who would sail to Zeeland in exchange for food and accommodation.

Expenses

The forced stay in the harbor of Plymouth cost quite a lot of money. The captain cashed two letters of exchange to pay the bill of about 60 pounds Sterling, almost 700 guilders – about 6900 euros (in 2013).

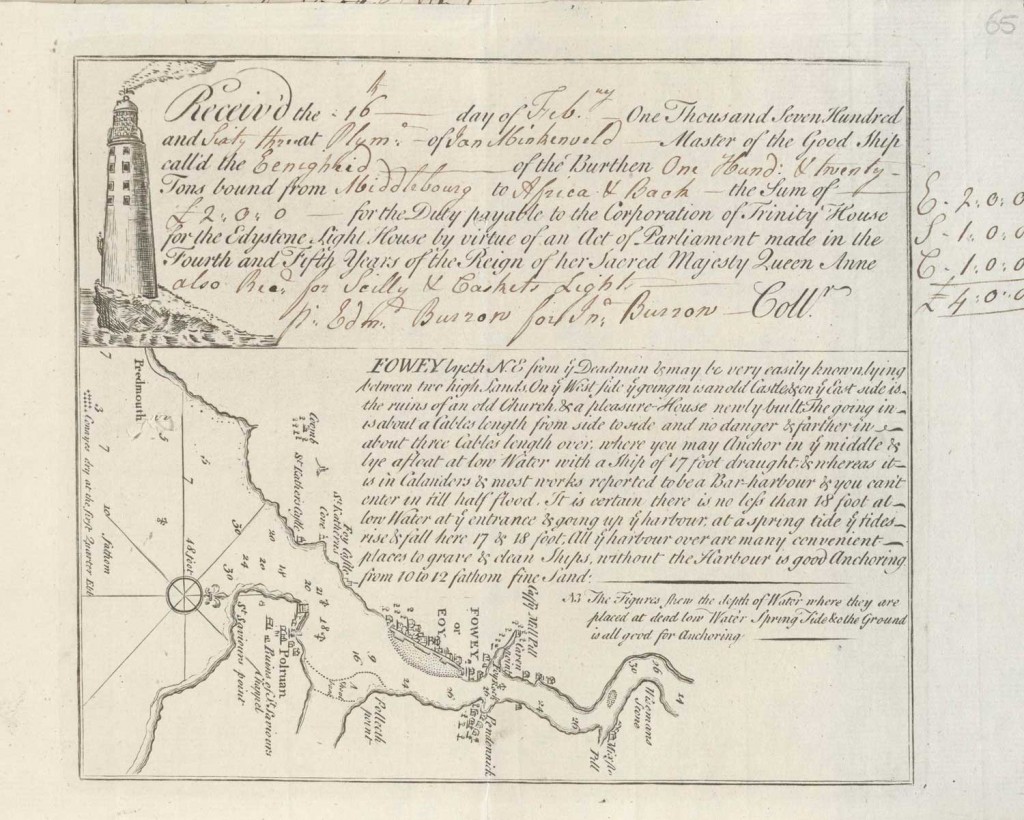

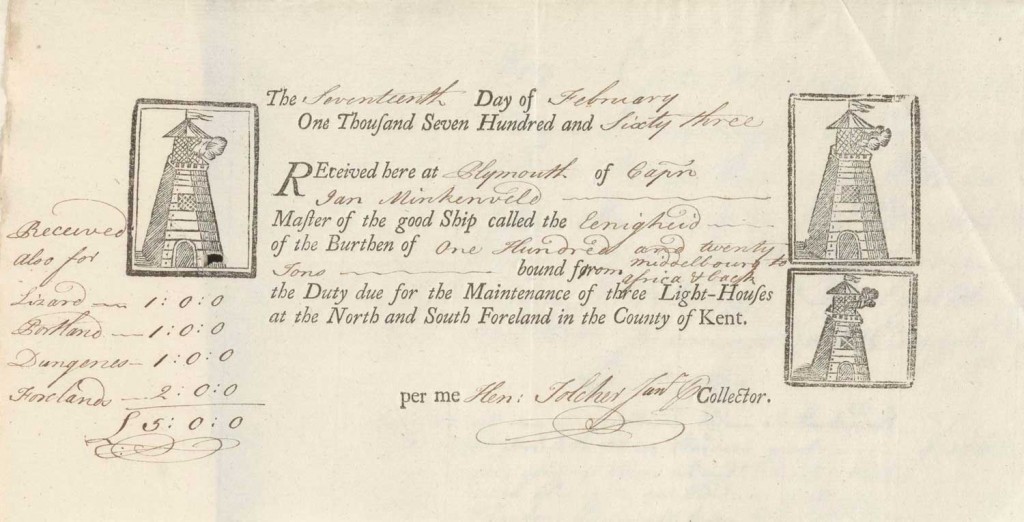

This bill included expenses such as harbor-, anchoring- and lighthouse taxes. The ship also need some reparations and maintenance, and the provisions for the crew had to be replenished. Captain Menkenveld bought drinking water, rum, vegetables, bread, cheese (about 27 kilos), green peas, beef (about 250 kilos), mutton, beer and butter.

Damages

The weather remained bad. The lost its anchor in the night of March 1st and 2nd, and drifted off, hitting another English ship. The bow sprits of the English ship damaged the carving on the transom of the ship. The captain could only just prevent the ship from running into shore by dropping his three other anchors.

So Close, and Yet So Far

The captain and his crew were more than done with the useless waiting around. When the weather improved slightly on March 3rd, 1763, the captain decided to leave. The next day a pilot entered the ship, and in the night the ship sailed and was towed away, out of the ‘Oostcoffer’ harbor. The boat and rowboat were taken on board in the morning, after which the pilot left the ship. Unfortunately the departure never got off the ground. Due to the weather, the last attempt had to be aborted at three in the afternoon. At four, a pilot came on board again to guide the ship back to the Plymouth harbor.

The next day, March 6th, 1763, The Unity sailed to another harbor in Plymouth, the ‘Westcoffer’. There the ship ran into problems on the 11th and 12 of March. It began to storm and again the anchors failed to hold the ship, grounding the ship. At low tide the depth measured at the bow was only 6 feet (about 1,70 meters), while at the back it measured a mere 2 feet (70 cm). The next day the weather improved a bit again, and the ship could be led away from the shore. All the time home remained close by, and yet so far off.

Successful Departure, then Beached

The next attempt proved successful: on March 19th 1763, the boat and rowboat were taken in, and the next day The Unity departed together with five Dutch and two Zeeland ships. The following days The Unity passed the isle of Wight, followed by the harbor of Dieppe along the coast of France. The pilot, Thomas Broad, boarded the ship near Dover. Next, the ship passed Lissewegen and the tower of Flemish Westkapelle, along the coast of Flanders. The ship reached the mouth of the river Westerschelde, and suddenly hit on the sandbank the Oosterrassen.

Meeuwensteen

Meeuwensteen or lighthouse Edystone near Plymouth. Etching and dry needle, John Clerk of Eldin, ca 1770-1782, 6×9 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Meeuwensteen

Meeuwensteen or lighthouse Edystone near Plymouth. Etching and engraving, Hendrik Hulsbergh after Isaac Sailmaker, 1733, 47.9×59 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Lighthouse fee

Receipt for payment lighthouse fees Edystone, Lizard, Portland, Dungeness en Foreland. Zeeland Archives, Archives of the MCC, inv.nr 389.3.

Letter of the captain

Letter of the captain Jan Menkenveld, 25 February 1763. Zeeland Archives, Archives of the MCC, inv.nr 376.