On 23 February 1763 the enslaved people in the Dutch colony of Berbice revolted. The population of Berbice consisted of roughly 350 Europeans and approximately 5000 enslaved Africans. Almost all of the Europeans fled from their plantations – forty of them were killed. It took more than 10 months to recapture the colony from the enslaved people, during which more than 1800 enslaved persons were killed.

The enslaved Africans who had arrived in the colony with the Unity in July 1762 probably witnessed the uprising first hand. This was especially the case for the European inhabitants who were involved with the Unity’s arrival. A number of them died during the revolt, while several officials were banned from the colony for their bad behavior and drunkenness by the government of the colony, as can be read in the following account of the Great Uprising of Berbice.

The small uprising of enslaved Africans

A small uprising of enslaved Africans took place on July 5th, on plantation Good Land and Good Fortune of Laurens Kunckler. A little over thirty enslaved Africans met their deaths during this revolt. Kunckler was one of the men who bought enslaved persons from The Unity – in fact, he bought the most. After the revolt had been put down the atmosphere in the colony remained unstable. Captain Menkenveld was requested to lend 6 cannons of the Unity to the commander of the fort. Logbook, 28 July 1762:

“We left our 6 breech pieces on the shore because the governor needed it for his land. After he had used them, he would send them after us on a different ship.”

Meanwhile, in the colony

On 16 September 1762 Wolfert Simon van Hoogenheim, governor of the colony Berbice, wrote a long letter to the directors of the Society of Berbice. (As governor of the colony, Van Hoogenheim represented the board). He wrote that the situation in Berbice was still very bad. The prevailing disease (probably dysentery) raged worse than ever before and had already claimed the lives of two of the council members Emmanuel Hosch and Charbon and several directors of the societal plantation. Because of this the Court of Police and Criminal Justice no longer had enough members to come together for meetings. He further noted that, except for ten men, all soldiers at the fort had passed away or were ill. He urged for more soldiers and European staff to be send to the colony. In two later letters, of 25 September and 25 November, Van Hoogenheim reported that there were virtually no provisions left in the colony. The reinforcements did not come on time.

Beginning of the revolt

So the colony was brooding. The enslaved Africans were hungry and were often the victim of severe punishments. On February 23 1763 the carpenter of plantation Magdelenenburg in the Canje Creek was murdered by rebelling enslaved Africans. Their leader was Coffy from plantation Lelienburg. This was the beginning of the Great Uprising. The rebels marched on to plantation Providence. Manager Joly could only just run off to plantation Stevensburg. The manager of plantation Stevensburg, Chambon, was a civilian officer of the Canje division, requested vainly for reinforcements.

Fleeing inhabitants

It only took a few of days before enslaved people on most of the private plantations were in full revolt. They violently forced the enslaved people of the societal plantations join them. On February 28 governor Van Hoogenheim received a message that the enslaved people on the private plantations Elisabeth en Alexandria, Hollandia en Zeelandia, Juliana and Leliënburg had killed all the European inhabitants and had proceeded to plunder and burn down the buildings. They had chosen plantation Hollandia en Zeelandia as their headquarters. The European inhabitants of the plantations fled without meeting any resistance to the society plantation The Pear Tree. Governor Van Hoogenheim decided to gather the few valiant men still left at Fort Nassau.

Captain Cook

Captain Cook of the ship de Adriana Petronelle had offered his help. The governor asked him to position himself at plantation The Pear Tree to offer support to the refugees. Captain Cook, however, changed his mind. He sailed just passed Fort Nassau where he loaded furniture and other valuable possession from the plantations onto his ship. Even the repeated requests and orders of the governor and the members of the Court of Police were to no avail.

Uprising well on its way

Because of all the meetings and requests valuable time had been lost. Plantation The Pear Tree was surrounded by rebels. By now sixty refugees, among whom were 21 women and children, had gathered at the plantation. On March 3, 1763 600 rebelling enslaved Africans began to attack The Pear Tree. The men on the plantation led by Johan George and Ambrosius Zubli were able resist the attack for over 24 hours. On March 4, however, they were overpowered.

Negotiations

Fatigued, lacking food and water and knowing that no help would come, they tried to negotiate a peaceful surrender with the rebels. The Europeans were initially allowed to leave the plantation, but they had hardly made it into the boats when the rebels broke the agreement.

Bloodbath

Many were killed in the fight. About ten made it to the other side of the river to flee to Fort Nassau. The men, women and children who were taken captive awaited a horrible fate. Because of the harsh ways in which many of the plantation owners had treated the enslaved people, the rebels knew no mercy. Some men were whipped to death, others had to watch how their wife and children were slaughtered before they were killed themselves. Surgeon major Jan Jacob Bass, who had conducted the examinations of the enslaved people on the Unity, was accused of poisoning the sick people at the hospital. He was skinned alive and then bludgeoned to death. After Johan George, his wife and his son had been killed, Coffy took his oldest daughter as his wife.

At the fort

The victory at plantation The Pear Tree gave the rebels extra courage to march on Fort Nassau. The men at the plantation had already heard of the massacre that had taken place from the mulatto Jan Broer. Reverend J.V.P. Ramring, who had been spared because of his relationship with God, had also arrived at the fort with the terrifying news. The fort was overflowing with fleeing plantation owners and other white inhabitants. The poorly maintained fort had neither the housing capacity nor the provisions and drinking water required for so many people. Furthermore it appeared that there were only 16 healthy soldiers with few weapons and ammunition.

Cowardly men

Abraham Wijs, orphan master of the colony and also the MCC contact person, had sought his refuge on one of the three ships along with secretary and fiscal master Harkenroth. Under the pretence of being ill both men occupied the ship, preventing its use in the defense against the rebels. Other officials stayed at the fort and refused to cooperate. The only person governor Van Hoogenheim could count on was the brave lieutenant Thielen. On 6 March the governor received a written request from the white inhabitants who had fled, asking permission to leave the fort and go to the river mouth with the boats. That same day the governor sent a letter to governor Crommelin of Suriname with an urgent request for help. The cry for help arrived three weeks later and would save the European population of the colony from total ruin.

Contact with the rebels

On March 8, the governor received a letter from rebel leaders Coffy and Accara. In broken Dutch they advised him to leave the colony with his ships as soon as possible. If Van Hoogenheim chose not to do this, he would have to fire three shots. This would be the signal for the rebels to attack. Coffy and Accara also wrote that the reason for the uprising was the mistreatment of some of the plantation owners. The ones mentioned by name were Barkey, Dell, de Graaff, Lentzing. After an emergency meeting with the Court of Police they decided to leave the fort.

Leaving the fort

Everybody went on board of the ship after which the fort was set on fire. Three days later, on March 11, the ships arrived at the society plantation The Daybreak. The situation on the plantation was still calm. The governor and the members of the Court decided to stay here, hoping they could make a stand until help would arrive. The captains of the ships, however, did not agree and the decision was made to sail further down the river till St. Andries station, opposite Crab Island in the estuary of the river Berbice.

St. Andries Station

The situation in which they found Post St. Andries was not much better than it had been at Fort Nassau. From all over het colony plantation owners had fled to the station. There was barely any food, water and shelter and many of the people suffered from fever or dysentery. Governor Van Hoogenheim immediately took action. He had the rain gutters repaired to catch rainwater, he sent groups with ships to plantations to get water and provisions and he gave orders to build a parapet around the camp. The situation was so bad that the governor, in consultation with the three members of the Court, decided to allow the captains of the ships leave. Furthermore, he asked everybody who was not willing to fight to leave the colony. Twelve men stayed behind to assist the 35 soldiers in the defense of the station.

Help

Van Hoogenheim decided to appeal to a higher authority: he wrote letters asking for help from the States General. On April 8 these letters were sent with the ships of amongst other captain Cook and did not arrive in the Netherlands until the 10th and 11th of July. However, more immediate help appeared from somewhere else. On March 28, 1763 a sail was spotted on the horizon. Around 4 o’clock in the afternoon the English ship the Betsy, commanded by captain George Buckmaster, anchored near St. Andries Station. The ship had come from Suriname and had around 100 soldiers on board.

Offensive

On March 30, the governor started sailing up the Berbice river with three ships. The enslaved Africans were driven back further and further. On March 31, the detachment anchored near plantation The Daybreak. Two days later, between 300 to 400 rebels attacked, an attack which Van Hoogenheim was able to withstand. The attach was led by Accara, to the dismay of Coffy, the other leader of the rebels.

Contact

After the attack of April 2, Coffy contacted Van Hoogenheim. He wrote him that he regretted the attack of Accara and that he was not after war. Coffy proposed to divide up the colony: one half for the Europeans inhabitants and one half for the enslaved Africans who had fought for freedom. This letter exchange lasted the rest of the month.

Storm van ’s Gravesande

Governor Storm van ’s Gravesande of the Essequebo and Demerara colony had heard of the uprising via refugee plantation owners who. He called in the help of the indigenous people of Guyana to prevent the rebels from retreating inland. The governor also sent word to, amongst others, the St. Eustatius colony. On May 3, the governor of St. Eustatius sent two ships with a total of 154 soldiers on board to Berbice.

Rewards

In an attempt to motivate the soldiers, governor Van Hoogenheim offered rewards. He offered ƒ 500,- for rebel leader Coffy and ƒ 400,- for Accara. For every rebel still alive a reward of ƒ 50,- was offered and for every dead rebel ƒ 20,-. Furthermore half of the value of the confiscated goods would be divided amongst the troops. This latter reward, however, was withdrawn after protests of the shareholders in the Netherlands who argued that these good weren’t spoils of war but property of shareholders or of the free plantation owners.

Attack on The Daybreak

On May 13, the rebels decided to attack the plantation The Daybreak. Although they outnumbered the Europeans, the defense on the plantation withstood the attack. This was because of the soldiers of the St. Eustatius ships. After repeated attacks the rebels were driven back by the guns of the ships. Lieutenant Thielen chased the rebels with a group of 80 soldiers. The number of deaths among the rebelling enslaved Africans was estimated at 100 men, while there were only 8 deaths among the Europeans.

Another enemy

After this defeat the rebels had somewhat lost their courage and they stopped attacking. The men at plantation The Daybreak, meantime, were dealing with another enemy. The illness that had already plagued the colony for 15 years started to take its toll once again. The majority of the newly arrived troops were already sick or had died. There weren’t even enough men left to man the ships. The illness took the lives of several of the captains, as well some members of the Court, Gillissen and Schermmeester. During this period Van Hoogenheim kept a journal in which we can read that during the months of July and September one person died of this disease almost every day.

Deserters

Another ship with around 70 soldiers had arrived from Suriname in June, sailing up at Courantyne river that formed the border between Berbice and Suriname. They had to make sure the rebels of plantation Magdalenenburg were not able to march up to Suriname in the east. The soldiers consisted of runaway French and German men. With the help of about 40 indigenous people, the group of soldiers had managed to attack and rout a rebel camp. When they were dividing up the booty however, they began to quarrel. The French and German soldiers mutinied, overpowering their officers. With the intention to join the rebels they went towards plantation Magdalenenburg. The rebels, however, could not believe that a whole group of European soldiers would want to join them so they decided to take them prisoner. 28 of them were immediately killed after which the rest were divided over the plantation to work as enslaved persons for the insurgents.

Back in the Netherlands

At the end of May 1763 the first news of the revolt had reached the merchants in Amsterdam. This message had been sent by captain Richard Robberts of the ship The Sisters, which had arrived at St. Eustatius. These merchants in turn informed the directors of the society of Berbice and asked them for help. Together they submitted an application to the States General requesting two war frigates with 600 men to be sent to the colony. The States General first decided to send the frigate St. Maartensdijk commanded by captain Maarten Haringman of the Zeeland Admiralty with 150 men. The ship left on July 23. On August 15, captain Evert Bisdom left with 150 men on frigate de Dolphijn, soon followed by captain Ludolf Hendrik van Oyen with 110 men on the snow ship de Zephyr.

Duke van Brunswijk

The States General called in the help of the Duke van Brunswijk Wolfenbuttel. The duke was a field marshal and commander of the military of the Dutch Republic. He was the guardian of the then young crown prince and stadholder Willem V. The duke investigated the cause of the uprising and interrogated the directors of Berbice. He also provided a plan on how to proceed. He proposed to send a corps of over 650 volunteer soldiers to Berbice. He estimated the costs to be around ƒ 706.000,-.

Volunteer corps

Lieutenant colonel Jan Marinus de Salve was promoted to commander of the volunteer corps on July 23, 1763. It would take another three months before the regiment had gathered near Naarden. On October 19 and 20, the men marched to Muiden where they sailed over to Texel. At Texel they were divided amongst four three-masters and two smaller ships. On November 6, the fleet left the roadstead of Texel, arriving a month-and-half later in Suriname, where intelligence about the situation in Berbice was gathered. On December 26, the fleet sailed to the colony Berbice.

Incident at Berbice

In the meantime something had also happened at Berbice. Captain Hattinga, already notorious as a drunkard, had again taken to the drink at St. Andries station, where he was in charge. Drunk, he left the station on September 19, 1763 with 15 men, and sailed up the Canje river. He ordered the men to shoot at all vessels and enslaved Africans they encountered, without finding out whose side they were on. Captain Van Rijssel was immediately sent over to St. Andries to take charge. Lieutenant Pronk was sent in pursuit of Hattinga with a small group of soliders. As soon as Hattinga was captured he was court-martialled: he was dismissed from all offices and banned from the colony.

Disagreement among the rebels

On October 19, 1763, governor Van Hoogenheim was told by a mulat who had fled from the rebels that there was a lot of disagreement there. Coffy, leader of the rebels, had been overthrown by a certain Atta, who had subsequently appointed himself governor of the rebels. Upon this defeat, Coffy had committed suicide.

Captain Haringman

On October 26 help finally arrived when captain Haringman entered the river Nassau with his ship St. Maartensdijk. Haringman remained at the St. Andries station, because he feared that the disease on the plantation The Daybreak would infect his men. On November 11 five officers and 171 men, including governor Van Hoogenheim and captain Haringman, sailed up the river Canje with captain Salvolani’s ship. They routed the rebels until the Stevensburg plantation, and here sixable group of soldiers was left behind. The communication lines with Fort Nassau were restored.

Even more troops

When Van Hoogenheim returned to The Daybreak on November 19 he received a report from the director-general of Essequibo and Demerary that the indians in that colony had fought and killed many of the rebels. On November 27th the two merchant ships which had been sent from the Republic by the directors of the Berbice colony arrived. That same evening captain Bisdom arrived with the frigate The Dolphin, and on December 5th, captain Van Oyen arrived with the snow ship The Zephyr.

Plan of attack

Together with captain Maarten Haringment governor Van Hoogeheim put together a plan of attack. The station at the Stevensburg plantation would remain manned wtih an office rand 56 men. Lieutenant Cormbie, with 30 sailors and 30 soldiers, would attack the rebels in the back on December 7 by sailing up the Demerary river. The remaining main force would attack the rebels via the river Berbice. This man force consisted of soldiers and ship crews on five ships: The Dolphin, the Zephyr, the Dolphin’s barque, two barques from St. Eustatius and the barque The Hope, which belonged the colony. A total of 380 soldiers and sailors came with.

The Attack

On December 19th the main force began sailing up the Berbice river. Seeing all this war and violence scared the rebels, and many of them surrendered immediately. The insurgents from the Cornelia-Jacoba, Hollandia and Zeelandia, Juliana, Leliënburg, The Peartree and Zubli’s Lust plantations feld towards the Markey plantation and the Hardenbroek plantation near het Wikkie creek. Governor van Hoogenheim attacked the last plantation with his troops, but his men had become overconfident. Instead of sending out a boat to scout the area, all the officers sailed together, ahead of their troops. The rebels had hidden themselves, and opened fire. Captain-lieutenant Smits, lieutenant Thielen and sub-officer Rees were killed immediately, while two sea officers and six sub-officers were seriously injured. The soldiers, now driven on by revenge, continued the attack. After a long battle, which claimed the lives of many soldiers and rebels, the Dutch troops were successful in routing off the rebels from the plantation. There he was greeted by lieutenant Crombie, who had succeeded in taken over the plantation via the Demerary river, a long trip through the forests and a bloody battle. On December 31 the governor sailed back down the river to the Hardenbroek plantation.

State troops

On January 1 1764 governor Van Hoogenheim received a report that six ships, carrying the 600 men sent by the States-General had arrived at the mouth of the Berbice river. On January 6 the governor arrived at the wrecked Fort Nassau. The next day he met colonel De Salve of the State troops. Together, they deliberated how best to end the champagne.

Expeditions

Van Hoogenheim went to The Daybreak plantation and colonel De Salve established his head quarters at New Amsterdam, by Fort Nassau. The state troops were parceled out to different locations. Four troops remained at Fort Nassau, three were sent to the Hardenbroek plantation at Wikkie Creek, one was sent to the Cornelia-Jacoba plantation at Wironje Creek and one to the plantation The Savonette at the upper-Berbice. By now the rebels had established themselves on the Good Land and Good Fortune plantation and its surroundings, near the Hardenbroek plantation. Several unsuccessful expeditions were undertaken. The Good Land and Good Fortune plantation was finally taken from the rebels. On January 26 1764 captain Van Oyen led a force of over 170 men to the Wikkie Creek, where rebel leader Atta had hidden with his men. After having conquered several small stations, Van Oyen ran into the main rebel force. These however, fled away immediately, abandoning their leader Atta. Atta did succeed in staying out of the hands of the troops.

End of the revolt

Head of the rebels Goussari and former rebel leader Accara surrendered to colonel De Salve. De Salve made good use of the situation by sending them back into the forests, with the order of convincing as many of the fleeing rebels as possible to return. They succeeded in bringing back a sizable number of rebels, but Atta was still on the run. In February captain Salvolani with his ship, two other St. Eustatius ships and the Suriname troops were sent away. Of the state troops the ship The St. Maartensdijk was sent back to the Netherlands, while the ship The Zephyr left for Demerary, and the ship The Dolphin remained in Berbice.

First round of executions and martial court

On February 25 governor Van Hoogenheim consulted with the only remaining member of the Police Court, L. Abbensets, in order to appoint Stubbeman and Sollicofre as new members of the Court. On March 2, one hundred of the over 800 rebels taken into custody had been sent to The Daybreak plantation for trial. The members of the court examined the rebels from March 2 till 14: of the 101 who were on trial, 53 were sentenced to death, 1 to a flogging, and 47 were acquitted. Of the 53 sentenced to death, 15 were burned alive, 16 were broken on the wheel and 22 were hung by the neck.

Final battle

Rebel leader Accabre, who had violently separated with the rebel leader Atta, had encamped near the Markey plantation. Together with between 200 and 300 Africans he had reinforced his camp with earthen ramparts. Colonel De Salve set out on an expedition in order to wipe out this final threat. On March 23 a troop of 52 men attacked from the right, two troops of 16 men each attacked from the left, and a troop of almost 60 attacked at the front. After a few hours the rebels surrendered. Accabre and his lieutenant Mars were captured, together with 81 men, while the rest managed tof lee. This marked the end of the armed resistance of the insurgents.

Rewards

Although many of the rebels eventually surrendered voluntarily, some were captured due to the promise of a reward. According to Van Hoogenheim’s logbook, members of the indigenous people were paid f 1074,- for rebels who were still alive and f 1080,- for 180 chopped off hands of rebels whom they could not captured alive.

Atta

Rebel leader Atta still wandered around in the area of the Wikkie Cree. Finally, a member of the indigenous people managed to discover his hide-out, and Accara and Goussari were sent after him. After a short fight they overpowered Atta, and on April 15 he was brought before the governor in chains.

Second Round of Executions

The members of the Police Court meanwhile had continued their investigations of the rising number of captured rebels. On April 27, 34 rebels were sentenced to death and 275 were acquitted. Of the 34 death sentences, 17 were hung by the neck, 8 were broken on the wheel and 9 were burned, 7 of these with a small fire. Governor Van Hoogenheim, who disagreed with the cruelty of these sentences, was continuously drowned out by the three other members of the Police Court, and could only look on.

Third Round of Executions

The directors of the Berbice Society had by now heard of the second executions. They were shocked by the high number of rebels sentenced to death. In multiple letters to the governor and the boards of the colonies they requested more leniency for the remainder of the rebels. They feared a mass murder, in addition to the fact that the loss of so many valuable laborers would harm the colony. The letters however, arrived too late. On June 16 a third execution took place, which led to the deaths of 32 more rebels.

Source: Netscher, P.M., ‘Geschiedenis van de koloniën Essequebo, Demerary en Berbice, van de vestiging der Nederlanders aldaar tot op onzen tijd’ (‘s Gravenhage 1888).

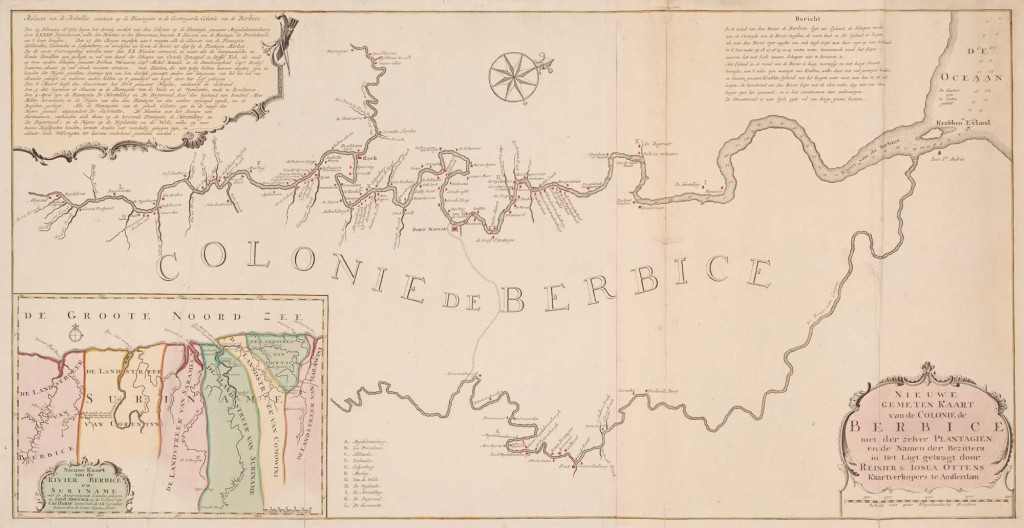

Berbice, Guyana

Map of the Berbice colony, with a story in cartouche about the slave uprising of 1763. Engraving published by Reinier and Josua Ottens in September 1763, 49×95.5 cm. Zeeland Archives, Zelandia Illustrata I, inv.nr 1625.

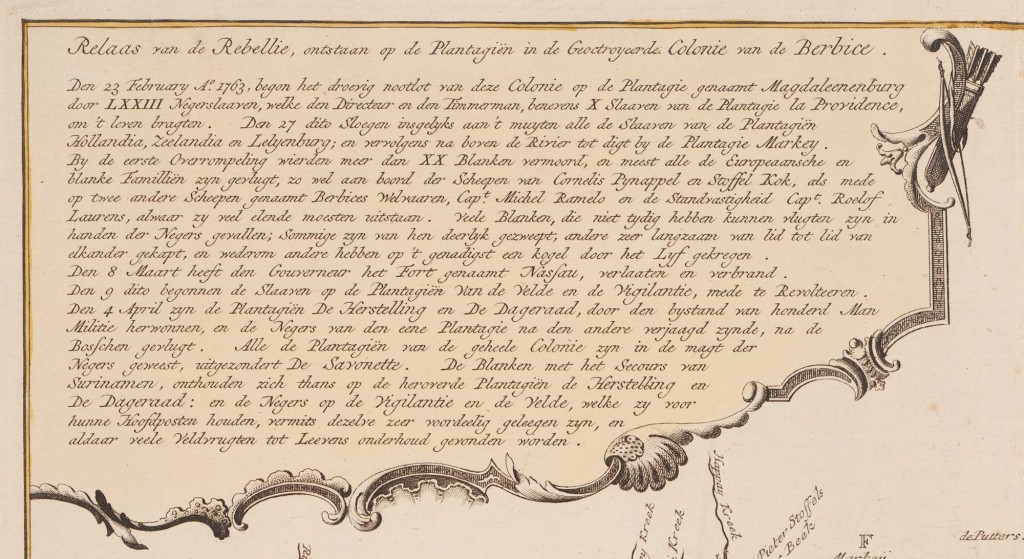

Story of the slave uprising on a map of Berbice

Zeeland Archives, Zelandia Illustrata I, inv.nr 1625.

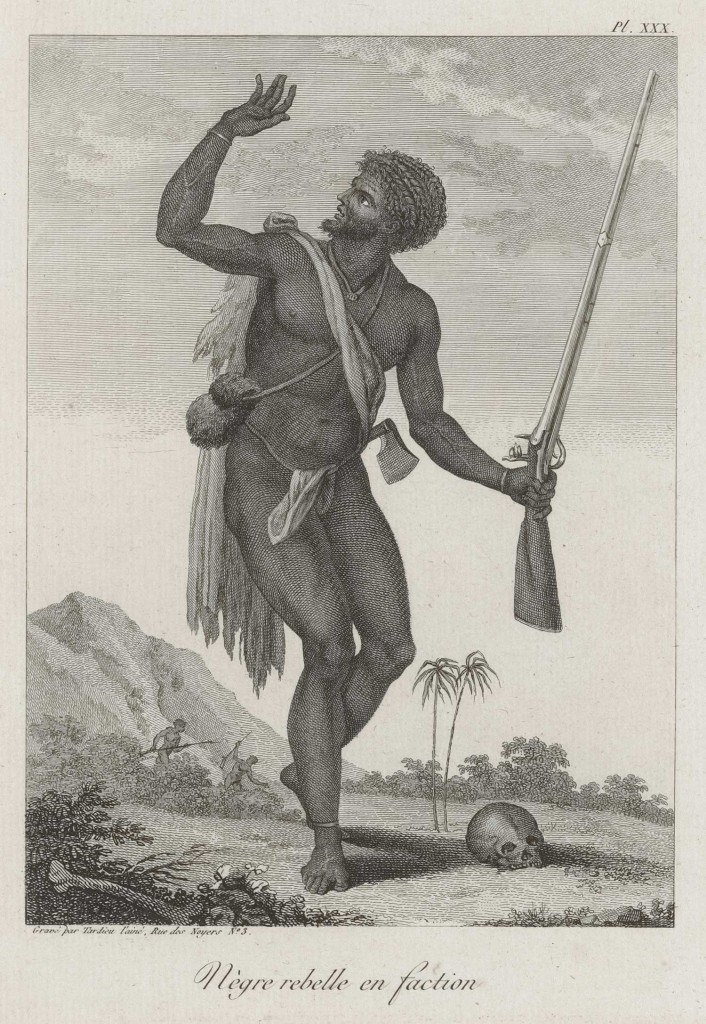

Rebel

Rebelling enslaved African, who after fleeing is fighting the white colonists. Engraving based on the drawing of (1744-1797) and a picture of William Blake by Tardieu l’ainé, in: ‘Voyage a Surinam […]’, Paris 1799. Zeeland Archives, Beeld en Geluid, inv.nr 589.

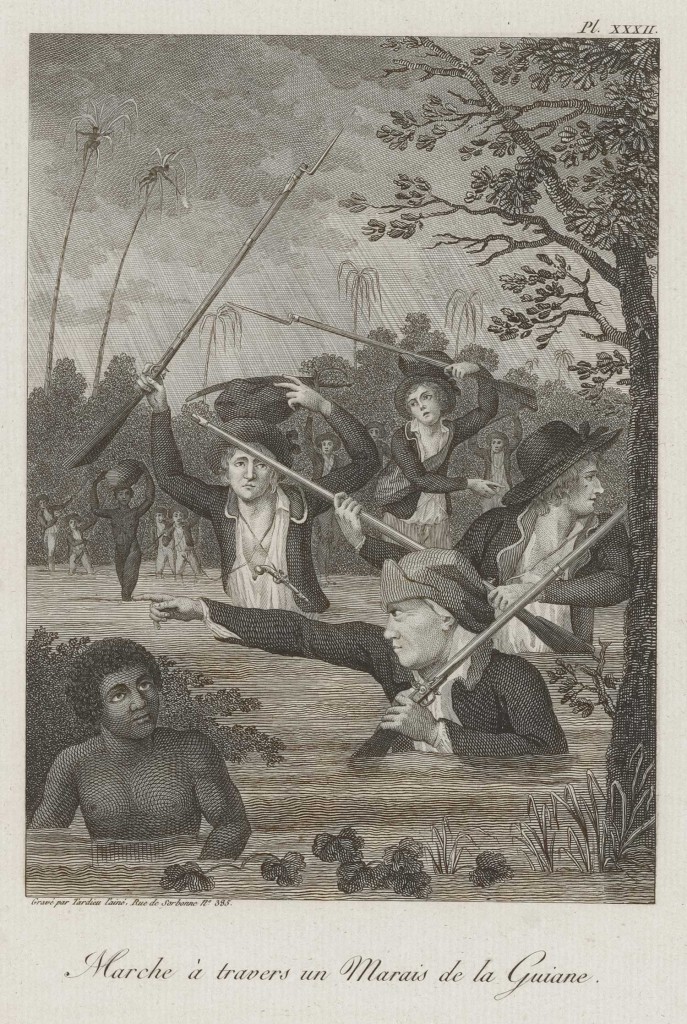

Military troops in the marshes

March of the soldiers in the marshes of Surinam. Engraving based on the drawing of J.G. Stedman (1744-1797) and a picture of William Blake by Tardieu l’ainé, in: ‘Voyage a Surinam […]’, Paris 1799. Zeeland Archives, Beeld en Geluid, inv.nr 589.